Hubert H. Humphrey Fellow Vyjayanthi Sankar’s Centre for Science of Student Learning aims to build capacity for high-quality assessments and research.

November 2019

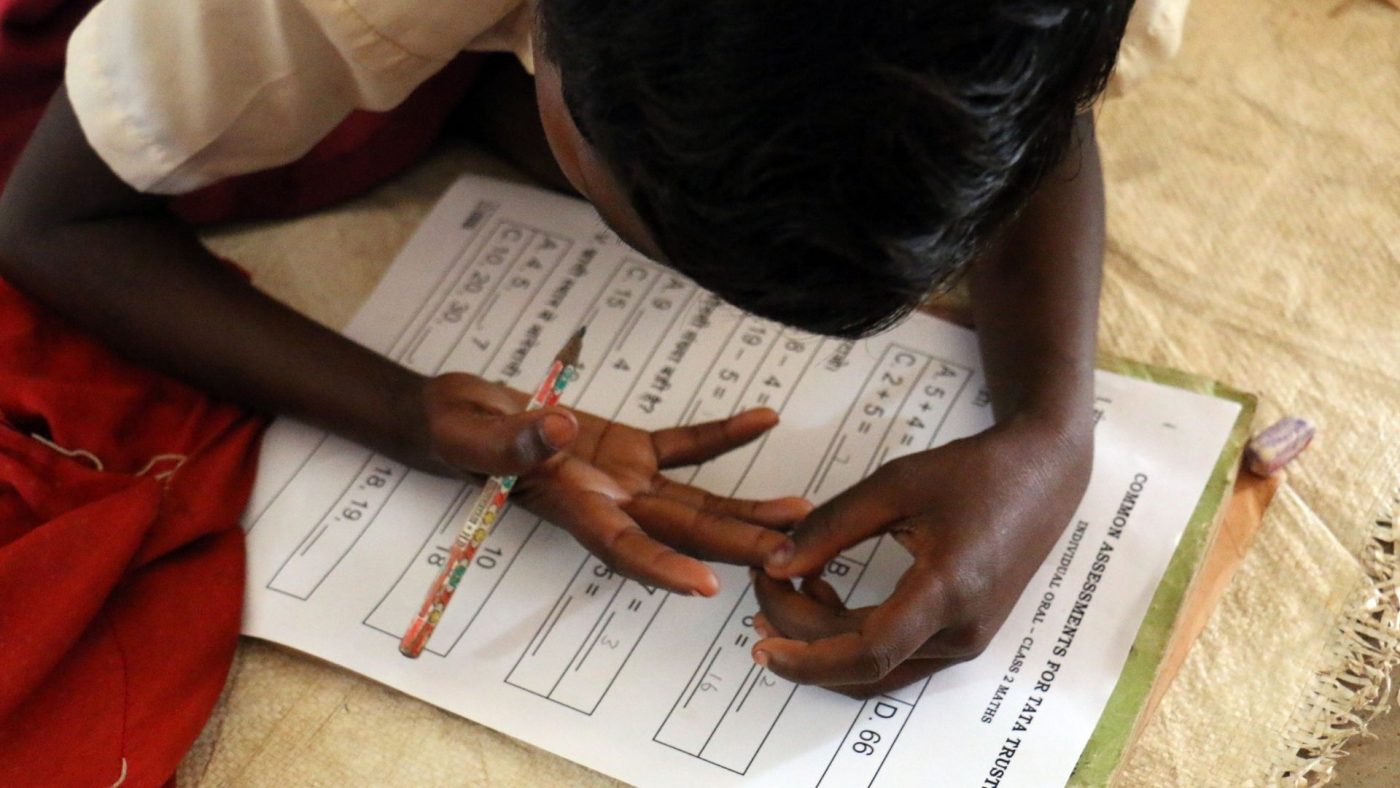

A student participant in a Centre for Science of Student Learning (CSSL) assessment. Photograph courtesy CSSL.

The education system in India, like in many other countries, lays a lot of importance on the number of students who pass school examinations and their scores. In the process, some schools focus less on what and how well the students learn. And, training for educational assessments and research into the science of how children learn is not widely available. There is a need for greater capacity to carry out the assessments that could shed light, in meaningful detail, on the gaps and misunderstandings in students’ knowledge. Even in the cases where sophisticated assessments are done, it is a challenge to analyze and use the results to improve the system of education and learning.

Vyjayanthi Sankar is working to change this scenario. She is the founder and executive director of the Centre for Science of Student Learning (CSSL). Founded in 2015 and based in New Delhi, the center tests students to help state governments and funders of education projects determine what students are learning and what difference various educational interventions are making.

Part of the reason why children are not performing better, says Sankar, is the emphasis on rote learning. It teaches children to memorize, but not necessarily to understand or be in a position to innovate and create.

Most school tests capture only what has been memorized. “Teachers are never taught how to build a good test—not for what they taught, but for what was learned by the students,” she says.

Sankar’s center has been working with seven state governments in India, carrying out student learning assessments and providing assistance on how to use the results. CSSL also provides short-term training for the states’ education officials to strengthen their capacity in this field. It is in talks with many other states, and is also considering extending its services to other developing countries.

At the same time, the center has created a master’s-level study program to train state government officials to run their own educational assessment initiatives and use the results to improve teaching. Currently, 11 education officials from Andhra Pradesh are enrolled in the three-year, practice-heavy program. They spend 60 percent of their time studying and 40 percent at their work, applying what they have learned.

Hoi K. Suen, a retired professor from Pennsylvania State University, where Sankar spent a year as a Hubert H. Humphrey Fellow in 2013-14, advises and oversees the master’s program.

Sankar credits her 10-month Humphrey fellowship with giving her the knowledge and confidence she needed to create CSSL. Sponsored by the U.S. State Department, the fellowship is an exchange program for young and mid-career professionals.

The fellowship allowed Sankar to deepen her understanding of learning assessment. It also gave her a more global understanding of professional, social and geo-political challenges. About 150 Humphrey fellowships are awarded annually, and they are hosted by 13 major U.S. universities. At Pennsylvania State University, for example, Sankar met several fellows from other countries. “We got to understand each other’s perspectives,” she says.

Besides carrying out assessments and training state education officials, CSSL carries out research into the science of learning. The goal here is to better understand how educators can support both academic and soft skills, like concentration, memory, self-image, emotional intelligence and communication—all of which can play a role in how well students learn.

In 2018, CSSL undertook a broad baseline assessment of grade-school student learning and common learning problems. The study was funded by the World Bank and commissioned by NITI Aayog, the Government of India’s policy think tank. “State governments use the results to provide training programs [to teachers] to improve teaching,” says Sankar, “and determine where students need remedial help.”

Burton Bollag is a freelance journalist living in Washington, D.C.

COMMENTS