Payton MacDonald, Fulbright-Nehru Academic and Professional Excellence Awardee, connects Indian classical music with Western musical traditions.

January 2020

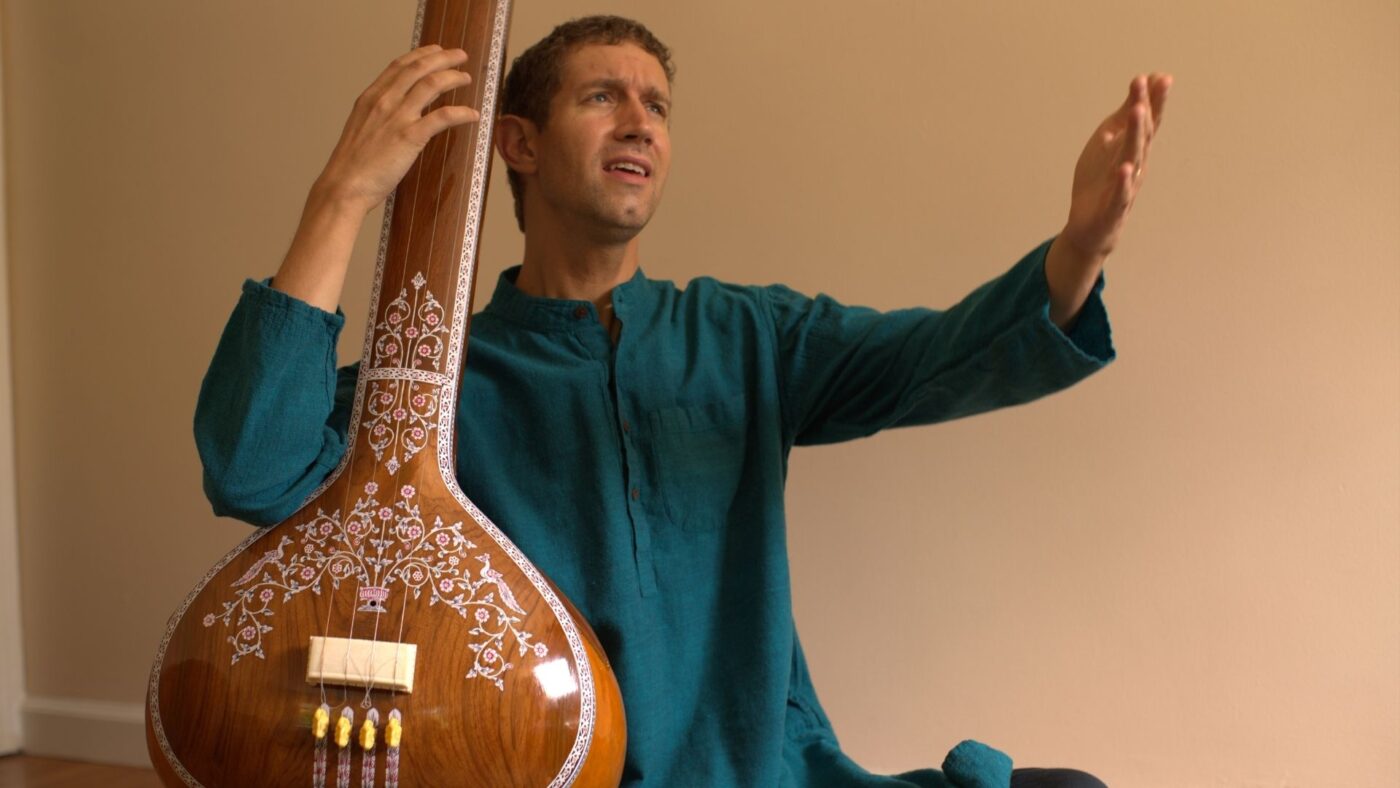

Payton MacDonald, a Western percussionist and composer, has studied the tabla and sings Dhrupad, a form of Hindustani classical vocal music. Photograph courtesy Payton MacDonald

Payton MacDonald travels effortlessly from the West to the East and vice versa in the world of music, absorbing different influences and performing across the world.

A Western percussionist and composer, he has studied the tabla and sings Dhrupad, a form of Hindustani classical vocal music. Currently a professor of music at William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey, MacDonald is also a Fulbright-Nehru Academic and Professional Excellence Awardee. His Fulbright-Nehru project in India aimed to improve his knowledge and practice of Dhrupad, while teaching a course on American experimental music composers who have been heavily influenced by North Indian classical music.

Excerpts from an interview.

How did you get interested in playing the tabla?

I first heard the tabla when I was 11 years old. I used to go to the Idaho Falls Public Library, where I found a large stack of LP [long playing] records with the likes of Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, G. S. Sachdev and many other major artistes of Hindustani music. My love affair with this music was immediate. I find it to be the most complete and satisfying form of music ever created. I learned the tabla for 10 years under Pandit Sharda Sahai of the Benares gharana.

What are some of the commonalities you find in the percussion instruments across the world, many of which you play?

Groove, touch, tone, the connection to dance, the spirit of rhythmic flow…The grammars are very different, but the underlying ethos is the same: getting the heart, mind and body to flow and dance.

How did you become interested in Dhrupad?

I was always attracted to Dhrupad, but never had access to teachers. In 2011, my tabla guru passed away. I was also having some physical issues with my hands and was thinking of going in a different direction. I had taken some group Khayal vocal lessons with Mashkoor Ali Khan. He and one of his American disciples, Michael Harrison, both commented that I have an excellent voice for Hindustani music and encouraged me to pursue it. I, then, serendipitously found out that Ramakant Gundecha of the famous Gundecha Brothers duo was teaching Dhrupad via Skype, so I started with that. My first six months with the gurujis were on Skype!

You were a Fulbright-Nehru Academic and Professional Excellence Awardee in 2013-14. Could you please tell us about your project in India?

I was awarded a research/teaching fellowship to spend nine months at the Dhrupad Sansthan in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. My award was 80 percent research and 20 percent teaching.

I took daily classes with my gurus, the Gundecha Brothers, learning all aspects of Dhrupad, including voice culture, raag structure, sur, swaar-sthaan, bandishes, upaj and much more. At the end of my time there, I made my debut as a Dhrupad singer at a concert at Bharat Bhavan, one of the main stages in Bhopal.

In terms of teaching, I shared my knowledge of Western classical music with students at the Gurukul. I presented approximately one lecture a week on a variety of topics. But mostly, I worked through the history and general theory of Western music. The Indian students were very attentive and had a lot of fascinating questions.

What were some of your key takeaways from the Fulbright-Nehru experience?

I can’t overstate how much the Fulbright experience changed my life for the better. Since returning to the United States, I’ve performed over 100 Dhrupad concerts and workshops, made four YouTube videos, and I’m now embarking on a project of four full-length Dhrupad audio recordings. I’ve exposed thousands of Americans to Dhrupad, trying to further my gurus’ mission of spreading Dhrupad around the world.

I still go back to India every other year for more taalim [training] and to perform. Going deep into sur opened my ears and my mind to an entirely new universe of sound, the primordial naad; something fundamental to the human experience. Singing Dhrupad every day is a kind of yoga, naad yoga, and the practice has focused my mind, calmed my body, and given me much strength through difficult times.

I also worked on my Hindi while I was there. I can read and write the Devanagari script, which has been most helpful in polishing my pronunciation of the bandishes. My speaking skills are still poor, but I work on it when I can.

It took me some time to get used to the cultural differences, but now I feel quite comfortable there. I have found Indian audiences to be very welcoming of me as a “foreigner” singing Dhrupad, and extremely supportive. The audiences can tell that I am committed to this art form for the rest of my life. I am not just a musical tourist.

I’m now performing as many concerts a year as a Dhrupad singer as I am as a percussionist. None of this would have been possible without the full immersion that I accomplished while on the Fulbright-Nehru program. I’m so glad that the U.S. and Indian governments continue to invest in this worthwhile program. I just hope that they invest even more over time. As our world becomes increasingly connected, it is more important than ever to foster intercultural dialogue in all disciplines.

How do you bring the Indian classical style of vocal and percussion into the Western musical tradition?

I use the rhythmic solkattu system almost every day with my students. I also teach classes on Indian music that include a lot of singing. So in that way, it is quite direct. I also frequently perform pieces that bring the traditions together in meaningful ways. For example, during this [autumn] semester, I’m conducting a piece I commissioned from Akshaya Avril Tucker, a very gifted American composer and cellist who has also studied Indian music and dance. Akshaya wrote a wonderful concerto for tabla and Western percussion quartet. I have a local Indian playing the tabla part and my students play the percussion parts. It’s a fabulous experience for everyone.

Do you feel, as a teacher, you have been able to infuse more interest among your pupils about Indian classical music?

Oh, for sure! Recently, the Dhrupad Sisters [Amita Sinha Mahapatra, Janhavi Phansalkar and Anuja Borude] were at our university. They were singing a bandish in Dhamar raag, all of my students were able to keep taal perfectly. In 2015, I took five students to Dhrupad Sansthan for a month of taalim with the gurujis. I’d like to believe that I have been able to get the student community at the university keyed into Indian music through my interactions.

Ranjita Biswas is a Kolkata-based journalist. She also translates fiction and writes short stories.

COMMENTS