Three Fulbright-Nehru fellows talk about their research in India and the incomparable exposure the exchange program offers.

January 2023

The Fulbright-Nehru Fellowship awards grants to U.S. college seniors, graduates and academicians at all levels to conduct research at a host institution in India. For many, this tenure allows them to form crucial relationships in closely-knit communities. Here, U.S. Fulbright student researcher Amelia Colliver (left) joins SECMOL (The Students Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh) in their annual apricot jam picnic. (Photograph courtesy Tashi Chotak at the Himalayan Institute of Alternatives in Ladakh)

The United States-India Educational Foundation (USIEF) organized the Annual Fulbright Conference in November 2022, the first such gathering of Fulbright-Nehru awardees in India after the COVID-19 pandemic. The conference hosted 110 American Fulbrighters over three days in New Delhi, during which they presented their research and networked with other academics.

The Fulbright Commission was signed into existence in 1950 by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and U.S. Ambassador Loy Henderson. Fifty-eight years later, in 2008, India became a full partner in the programmatic funding of the exchange program, now known as the Fulbright-Nehru program.

The U.S. Fellowship awards grants to U.S. college seniors, graduates, academicians at all levels to conduct research at a host institution in India and carry out professional projects mentored by Indian academic supervisors. During their tenure, the Fulbrighters apply their expert knowledge of a field to the Indian context, study real-time issues and learn from their counterparts in respective fields. For many, this tenure brings invaluable exposure as they work with closely-knit communities, allowing them to form crucial relationships.

Mariam Alkattan

Do you self-medicate with antibiotics for common colds or mild fevers? Have your antibiotics stopped being effective? Research has found that India has one of the highest rates of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the world. This means more and more people will not respond to antibiotics when they fall sick. At the same time, no new antimicrobials are being developed to treat drug-resistant infections.

For Fulbright-Nehru Student Researcher Mariam Alkattan, this was an opportunity to study AMR in India and spend the next nine months setting up a research lab from scratch. Alkattan has a Master of Science in environmental engineering from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She was hosted by the National Forensic Sciences University in Gandhinagar, where she started her Fulbright-Nehru tenure in April 2022.

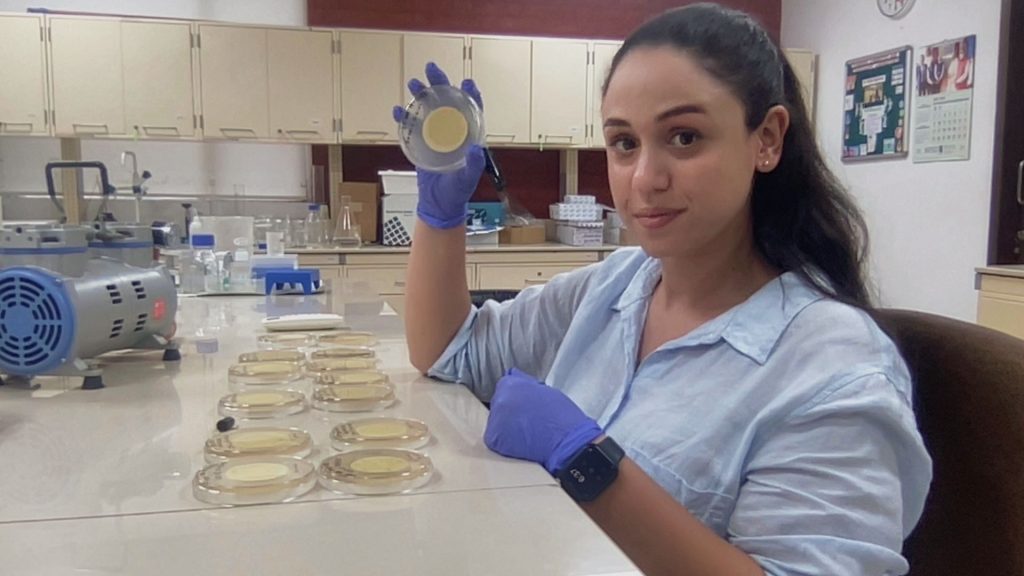

Mariam Alkattan’s research involves sampling water bodies around Ahmedabad to check for biological contamination and drug resistance. (Photograph courtesy Mariam Alkattan)

A large part of Alkattan’s research involved sampling water bodies over several months in and around Ahmedabad to check for biological contamination and drug resistance. The team found that out of the almost 100 water samples they collected, every sample contained resistance to at least one of the drugs they were tested against. In addition, many of the samples were resistant to multiple drugs, a significant finding that implies infections that are more difficult to treat.

Contamination of water bodies by human and animal waste, crop pesticides and pharmaceutical waste has wide ramifications for those who use these water bodies as sources for drinking, cooking or washing, and leads to AMR mutation and creates antibiotic resistance.

Even though the study of AMR has a long way to go in India, according to Alkattan, her research aims at creating standardized testing for AMR. “We don’t even have a standard method [to measure AMR]. With our research, hopefully, we’ll be able to provide information on accuracy and ease of use of tests.”

Alkattan spent the first few months of her fellowship learning things she had never been taught before. “I had to learn from reading the available literature, and create a research program from scratch,” she says. “This was incredibly difficult, but something I could only do with Fulbright; it gave me the time and freedom to do that.”

Alkattan hopes to establish some groundwork on AMR before she leaves India. “I hope the payoff of doing something so complicated is that we have a foundation of data and methods for scholars to continue AMR research ” she says. Alkattan leaves behind the lab, which was not there when she arrived.

She has also created some fun memories in the process. “While collecting samples in Ahmedabad, one site was really close to an ice cream shop. So, we used to go to ‘sample’ the ice cream,” she giggles.

Going forward, Alkattan hopes, through her work, to “share information on best practices and inform policy regarding environmental AMR.”

Lydia Fisher

Lydia Fisher was 21 and a junior at Bryn Mawr College when she came to India–and New Delhi–as a member of her study abroad program SIT: India (School for International Training). Having grown up in Unionville, Pennsylvania–a small town outside Philadelphia with a population of about 600 people–Delhi’s air and noise pollution came as a shock to her, she says. But she wanted to know more about the people and their environment and it brought her back to India three years later, this time as a Fulbright-Nehru Student Researcher.

At Bryn Mawr, Fisher majored in international studies with a focus on environmental and public health issues. She has been in India since March 2022, researching the effects of air and noise pollution on the human body and society. She is affiliated with Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) in Mumbai and advised by Dr. Amita Bhide. Her air pollution work is focused on the residents of the M-East Ward—a municipal area in Mumbai and home to one million people. The area is also home to a range of major air pollution sources, including Asia’s largest garbage dumping ground and the largest biomedical waste facility.

Fisher says her work revolves around studying air quality, monitoring and governance, and looking through regulations. Her research, says Fisher, will inform policy on air pollution education and the treatment of air pollution-induced health issues. “The human body breathes 11,000 liters of air every day. Our research is to find out what exactly is in the air that people are breathing,” she says.

Lydia Fisher (second from left) says her work revolves around studying air quality, monitoring and governance, and looking through regulations. (Photograph courtesy Lydia Fisher)

Research has found that perception of air pollution has a major impact on decisions on exposure, and is usually studied in social and economic contexts. For example, a person who usually stays in an air-conditioned environment might find a five-minute exposure to outdoor pollution more uncomfortable than a roadside vendor, even though the effects of the pollution on the body are the same in both cases.

The second component of her research—noise pollution—focuses on the effect of elevated street noise on residents and traffic police in Mumbai. Mumbai is one of the loudest cities in the world and Fisher says ambient street noise averages around 70 to 80 decibels. Traffic cops bear the brunt of this noise with horn blasts and vehicles coming at them from every direction. Fisher says her work investigates the health consequences of exposure to elevated traffic noise in their daily work, contextualized by their understanding of the issue and their access to treatment.

Fisher says long-term exposure to high noise levels leads to hearing loss and stress as well as an increased risk of hypertension and diabetes. “There is a lot of research on this, but most of it comes from Europe and the United States,” says Fisher. But, she explains, noise and its effects on people have to be studied in social and cultural contexts. For example, she says, hearing loss is related to genetics, environment and exposure. “And India has a very high rate of hearing loss,” she explains.

Currently, Fisher is working on a survey of 400 residents of the six settlements in the north of M-East Ward. The survey investigates indoor and outdoor air pollution health effects, treatment choices and trends at the local level.

Vani Dewan

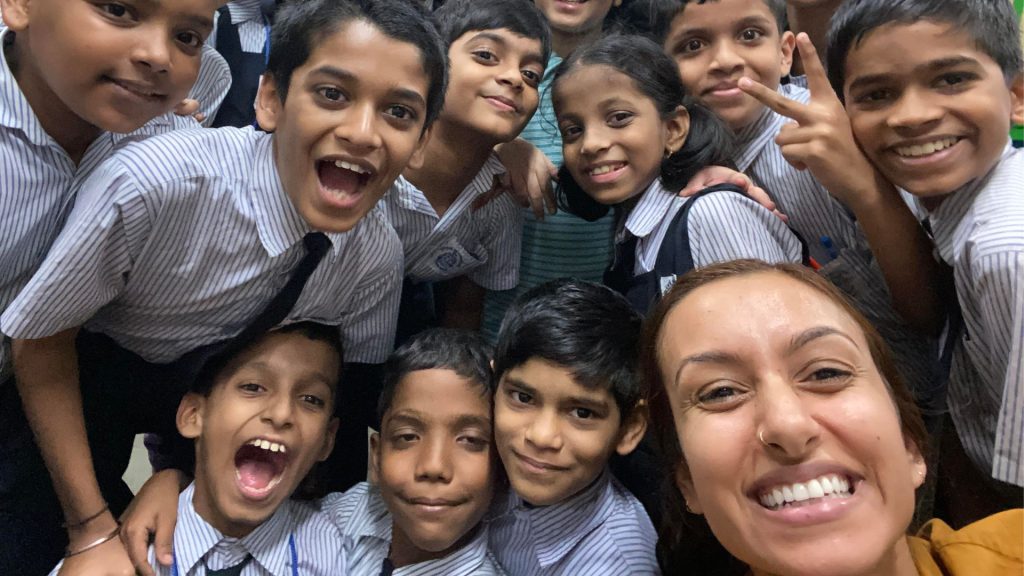

Mumbai-based Vani Dewan is a Fulbright-Nehru Student Researcher, studying the neurological connections between early-life stress and its effect on mental and physical health across a lifetime. When not in the lab, she spends her time DJing in Mumbai clubs, teaching choir to students at the Muktangan school, which involves lessons in breathing, posture, enunciation, tone, emotion, storytelling and more.

Dewan graduated from Scripps College in California in 2021, with a degree in neuroscience. She is hosted by the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, where she works at neuroscientist Vidita Vaidya’s Neurobiology of Emotion lab.

The lab is involved in rodent research to find how early-life stress can create physiological changes in rodents, and the potential effects of pharmaceutical and psychedelic therapies in such cases. “Understanding this connection between psychological and physiological phenomena has blown my mind,” she says. Rodent research is beginning-of-the-pipeline work, findings of which get extrapolated on humans following years of subsequent research, explains Dewan.

The lab where Vani Dewan (right corner) works is involved in rodent research to find how early-life stress can create physiological changes in rodents. Here, she is pictured with students of the Muktangan school, where she teaches choir. (Photograph courtesy Vani Dewan)

Dewan is grateful for the experience and independence the Fulbright-Nehru program has brought to her. “Being financially independent in the first year after graduation is a very big deal for me,” she says. “I’ve been able to completely self-sustain this entire year.”

She says the Fulbright-Nehru program has put her in the space of mental health and neuroscience research that she wouldn’t have been able to access on her own.

On the personal front, she got a chance to dabble in DJing. “DJing here has been a joy. All my favorite musical genres are pretty well represented here in Mumbai,” she says.

Though her tenure in India has been of just nine months, Dewan takes back with her invaluable experience and memories. Most importantly, as an Indian American, Dewan says the time in Mumbai has added more depth to her identity. “I realized how American I am after spending time in India,” she smiles, but adds, “I will return to the United States more Indian than I ever was before.”

COMMENTS