Historic sites, such as those from the LGBTQIA+ rights movement, embody the past and serve as a critical context for visitors to understand the efforts, clashes and advances over time.

December 2021

National Park Service rangers with the Stonewall National Monument place rainbow flags along a fence in June 2019, part of activities marking the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising in New York. Photograph by Craig Ruttle © AP Images

The LGBTQIA+ rights movement in the United States has paved the way for marriage equality, anti-bullying measures in schools, and the ability to serve openly in the military; but, many people are unfamiliar with the pioneers who fought for these social advances.

Over the decades, committed activists have worked to increase awareness of historic LBGTQIA+ sites, which emblemize past struggles and serve as a critical context for visitors to understand what happened in their collective past. We invite you to take a tour of some of the United States’ historically representative sites from more than 200 years of LGBTQIA+ history.

Stonewall National Monument, New York

Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell speaks at the dedication of the Stonewall National Monument at the Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village on June 27, 2016. Photograph courtesy U.S. Department of Interior

The modern LGBTQIA+ movement in the United States started at the Stonewall National Monument in Manhattan’s West Village. The Stonewall Inn was a gay bar that sold liquor without a license at a time when being openly gay was against the law. Police raids were a common way to target the gay population. Bar patrons were arrested, photographed and outed in local newspapers, severely impacting their lives.

On June 27, 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn. The local community spontaneously rebelled against what they saw as unjust targeting, trapping police inside the bar and sparking a decades-long advocacy movement that culminated in countless civil rights advances.

Today the Stonewall Inn again thrives as a gay bar. It became a national historic landmark in 2000; and in 2016, President Barack Obama designated it as a national monument.

Harvey Milk Plaza, San Francisco, California

The Harvey Milk Plaza at the corner of Castro and Market Streets in San Francisco. Photograph courtesy @HarveyMilkPlaza (Instagram)

Harvey Milk moved to San Francisco’s Castro district in the 1970s and quickly became known as its informal mayor, thanks to his gregarious personality and advocacy for inclusion. He and his partner ran the Castro Camera shop at 575 Castro Street. Outside of the shop, Milk was a gifted activist dedicated to giving a voice to everyone who didn’t have one. He became a city supervisor in 1978, one of the top leadership roles in San Francisco’s government. Later that year, Milk and fellow progressive Mayor George Moscone were both assassinated inside the City Hall building by a disgruntled former city supervisor. The assassin’s light prison sentence resulted in the White Night riots, where the San Francisco’s community marched from the Castro to City Hall. Today, Harvey Milk Plaza at the corner of Castro and Market Streets, the heart of San Francisco’s LGBTQ community, pays homage to Milk’s legacy. A rainbow flag waves over the plaza, which also boasts a neon sign reading “Hope Will Never Be Silent.”

The Palace, Miami, Florida

The Palace bar rests on the famous Ocean Drive in Miami. Photograph courtesy @styleblueprint (Instagram)

Since its opening in 1988 in Miami, The Palace has become one of America’s most famous drag bars. The city has been home to a thriving LGBTQIA+ community for years but became a hotspot in the 1970s. Miami is famed for its nightlife and boisterous Pride parade. But before this, violence against LGBTQIA+ communities and police raids on gay bars were common. For example, politicians distributed anti-human rights misinformation, such as the infamous “Purple Pamphlet,” to raise illegitimate fears about queer people. However, by the 1980s, the glamorous Versace Era had begun in Miami. Glittering celebrities like Gianni Versace descended on the Miami beaches, and extravagant parties and drag brunches became commonplace among Miami’s trendiest celebrities. The local gay community, including co-founders of the Miami Design Preservation League Leonard Horowitz and Barbara Baer Capitman, fought to preserve South Beach’s Art Deco architecture and iconic color palette. The gay community in Miami was also involved in political activism for equal rights leading to monumental efforts such as the passing of an anti-discrimination ordinance in Dade Country in 1977.

Butt-Millet Memorial Fountain, Washington, D.C.

The Butt-Millet Memorial Fountain near the White House in Washington, D.C. Photograph by Tim Evanson/Flickr

The Butt-Millet Memorial Fountain, which stands near the White House, honors Major Archibald Butt and his housemate, artist Francis Millet. Butt and Millet were believed by some to be lovers. Butt, a confirmed bachelor, was a military aide to U.S. Presidents William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt. Before Millet became an artist, he was a drummer boy in the Civil War and a news reporter during the Spanish-American War. He had a wife and children but lived with Butt when in Washington.

The pair became inseparable, and when they traveled to Europe, they booked a first-class passage home on the Titanic’s maiden voyage. They perished at sea when the Titanic sank in 1912. After the horrific event, President Taft approved a memorial fountain designed by Daniel Chester French, who sculpted the Lincoln Memorial. Taft was said to have mourned Butt like he was a close family member.

Dr. Franklin Kameny Residence, Washington, D.C.

Dr. Franklin Kameny’s Residence in Washington, D.C. Photograph by Farragutful/Wikimedia Commons

A key figure in the gay rights movement, astronomer and military veteran, Dr. Franklin E. Kameny, was fired from his government job in 1957 when he declined to state his sexual orientation. Kameny argued that his sexual orientation did not affect his suitability for federal service and fought to reverse the stigma that cast homosexuality as a mental disorder. He became the first openly gay man to run for Congress. In 2011, his residence in Washington, D.C. was designated a national park, being the central hub of his efforts, as well as the Mattachine Society advocacy group, which he founded.

Henry Gerber House, Chicago, Illinois

The Henry Gerber House in Chicago. Photograph by Shirley and Norman Baugher/National Park Service

The Henry Gerber House was the first advocacy organization for gay rights in U.S. history, publishing the first advocacy newsletter. It was also home of the Society for Human Rights, founded in 1924 by Henry Gerber, when he was a tenant in the house. Gerber modeled his organization on the burgeoning gay subculture he discovered serving in the military in Germany after World War 1. He was arrested the year after he started the society, when police raided the house and took his typewriter, diaries and writings. Only his typewriter was returned. His home in Chicago is the second National Historic Landmark recognized in LGBTQIA+ history.

Matthew Shepard Memorials, Laramie, Wyoming and Washington, D.C.

A rainbow flag waves outside the memorial service for the interment of the ashes of Matthew Shepard at National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Photograph by Victoria Pickering/Flickr

Matthew Shepard, at the time, a 21-year-old college student, was targeted and killed in Laramie, Wyoming, in 1998 for being gay. His two attackers met him in a bar and pretended to be gay, hoping to rob him. They kidnapped, beat him, stole his wallet and shoes, and left him tied to a fence in freezing weather. He was discovered the following day, near death. Shepard spent nearly a week in a coma before dying.

The subsequent trial was a landmark case. His attackers claimed they assaulted Mr. Shepard in a state of violent, temporary insanity but the judge and jury rejected the argument. The nation experienced collective grief, with many understanding, for the first time, the plight of gay people. A new generation of activists was energized to fight; in 2009, a federal hate crime bill expanded the definition of a hate crime to include attacks on LGBTQIA+ people.

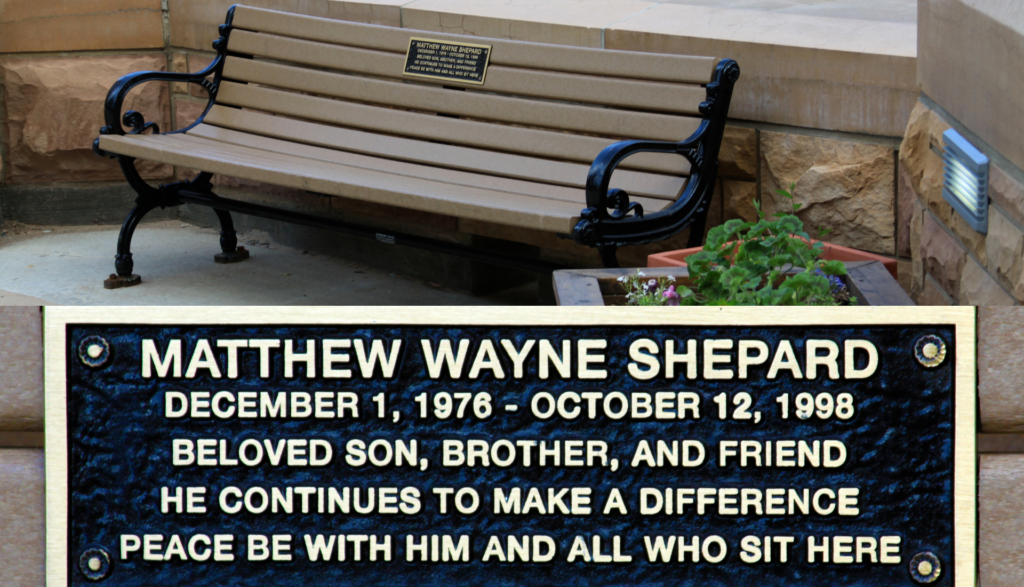

A memorial bench sits on the campus of the University of Wyoming in his honor. The university installed the bench a decade following Shepard’s death, at a time when acceptance of gay people had become more commonplace. A second memorial to Shepard can now be found at Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., where Shepard’s remains were transferred on the 20th anniversary of his death. The cathedral also has been the site of the funerals of many U.S. presidents.

The Matthew Shepard Memorial Bench on the campus of the University of Wyoming in 2010 and a close-up of the inscription. Photograph by Wyoming_Jackrabbit/Flickr

A Hopeful Future

Historic LGBTQIA+ sites tell important stories and introduce new generations to the struggles and victories of those who came before them. They represent the challenges and successes of the LGBTQIA+ rights movement, and normalize and celebrate the lives of people once misunderstood in America.

Candice Yacono is a magazine and newspaper writer based in southern California.

COMMENTS