Bilateral cooperation between the United States and India in health and biomedical innovation has had impressive results, but it holds the promise of even better outcomes and further innovations in the years to come.

January 2021

U.S. and Indian partners helped expand the polio immunization program, which eventually led to India becoming polio-free in 2014. Photograph by CDC Global/Flickr

Driving innovation to solve the health and biomedical challenges facing our citizens and those of other countries is one of the oldest and most successful areas of cooperation between the United States and India. This success reflects the best that our two countries can achieve together, and has improved the lives of millions of people in India, the United States, and around the world.

Our national governments, state and local authorities, civil societies, and private sectors have all played important roles in this partnership. Our joint achievements in health have benefited directly from the dynamic contributions of many segments of our societies, from academic and non-profit institutions to private individuals, charitable entities, and religious organizations. Together, the United States and India have been leaders in driving path-breaking research and innovation, and expanding the accessibility of quality health services to vulnerable populations.

Bilateral cooperation between the United States and India in health and biomedical innovation has had impressive results, but it holds the promise of even better outcomes and further innovations in the years to come.

A Long History of Cooperation in Health, Led by a Range of Individuals and Institutions

Bilateral cooperation in health dates to well before India’s independence. Gordon Hall, an American priest who had also studied medicine, set up the American Marathi Mission in Mumbai in 1813 to distribute medicine and health textbooks. Over the next 150 years, the American Marathi Mission assisted in the establishment of health institutions across India. In 1918, Dr. Ida Scudder, who grew up in India as a third-generation American medical worker, opened India’s first medical school for women at the Christian Medical College Vellore – one of the first schools in India to accept female medical students. The institution remains one of India’s finest to this day.

Health and biomedical ties have expanded since Anandibai Joshee (left) and Gurubai Karmarkar (right) traveled to the United States to study medicine and now form an important component of the U.S.-India Comprehensive Global Strategic Partnership. Photographs courtesy Wikipedia

Americans have also long been exposed to and benefited from India in the areas of health and medicine. In the 19th century, Americans started importing Ayurveda medicines from India, and Indians began studying medicine in the United States. Two young women, Anandibai Joshee and Gurubai Karmarkar, helped blaze this path when they enrolled at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in the 19th century. In the 1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation began organizing workshops in India on communicable diseases and other aspects of public health, and in the 1930s helped establish the All India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health.

U.S.-India health cooperation expanded significantly after India’s independence, focusing on some of the world’s most pressing health challenges. Beginning in the 1960s, joint efforts in the public and private sectors, including by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and Indian and international partners, led to the eradication of smallpox in 1977. In the early stages of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, U.S. and Indian scientists, policymakers, and non-governmental organizations established new prevention and treatment protocols to combat the disease. In 1995, USAID and the Indian National AIDS Control Organization signed their first joint agreement to combat HIV/AIDS, a collaboration later formalized with USAID, CDC, and the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Since 2005, the United States has committed nearly $360 million to support the Indian National AIDS Control Program under PEPFAR.

U.S. collaboration with Indian partners played an important role in the expansion of the polio immunization program in the early 1980s, which eventually led to India becoming polio-free in 2014, and subsequently maintaining its polio-free status. Starting in 2004, the CDC has supported India’s Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response plan and worked to strengthen surveillance networks and response measures across India. USAID and the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare have worked together for many years to better serve the urban poor, including by helping shape India’s National Urban Health Mission in 2013. In total, the United States has provided more than $1.4 billion to support India’s health priorities during the last 20 years.

2015-2020: Expanding Health Diplomacy and Cooperation

In recent years, the United States and India have showcased during high-level government meetings their work together on health and biomedical innovation. Joint statements following the official visits to India of Presidents Barack Obama and Donald J. Trump, and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to the United States, have all highlighted health cooperation, demonstrating the significance of this component of the bilateral relationship.

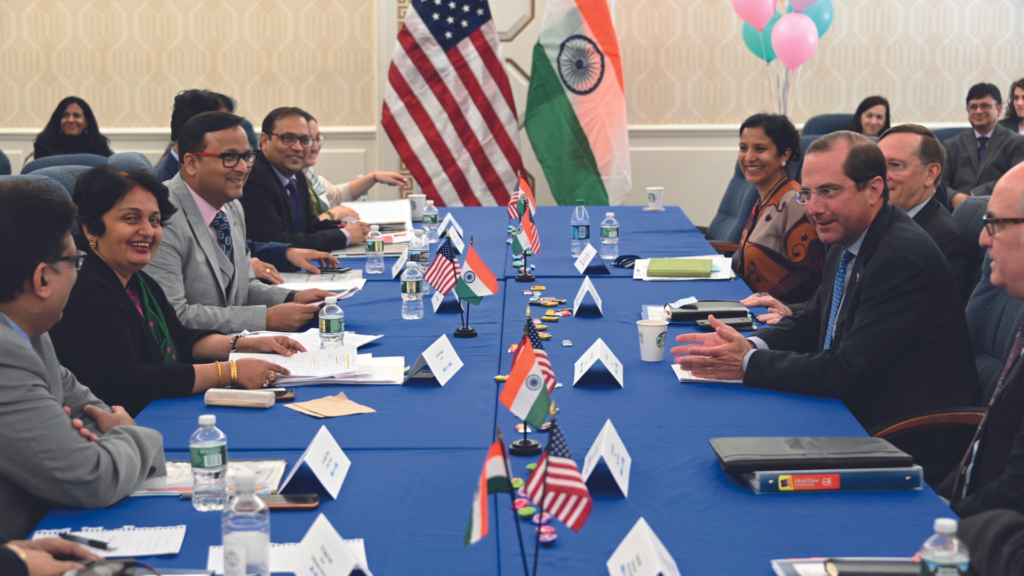

The U.S.-India Health Dialogue in Washington, D.C. in 2019. Photograph courtesy U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Echoing the vision set by our leaders, U.S. and Indian officials have strengthened the partnership across our governments, including through structured dialogues. In 2015, the United States and India held the first bilateral Health Dialogue, which addressed issues as diverse as infectious diseases, cancer, and mental health. In 2019, the Health Dialogue addressed six thematic areas of cooperation – research and innovation; health safety and security; communicable disease; non-communicable disease; health systems; and health policy – and facilitated the signing of several agreements.

The U.S. government has bolstered this health diplomacy with exchanges of scientists and health professionals. Since 2016, the CDC has brought Indian public health practitioners to the United States to participate in the Public Health Emergency Management Fellowship. The U.S. National Cancer Institute brings Indian cancer scientists, researchers, and experts to the United States to work alongside its scientists. In 2020, the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, signed an agreement with the Indian Council of Medical Research to establish a clinical research fellowship program for early career Indian and U.S. scientists focused on infectious diseases and immunology. And U.S. Embassy New Delhi has enabled dozens of Indian public health experts to travel to the United States to work on pandemic preparedness, environmental health, biomedical innovation, and other issues through the International Visitor Leadership Program.

Government-Supported Research Drives Innovation and Progress in Health

The U.S. government’s support for research on health in India has contributed to significant innovation and progress, complementing the non-profit and private sector health cooperation between our countries. For decades, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) have supported research in India on a range of issues, including communicable and non-communicable diseases, environmental health, the development of vaccines and therapeutics, and complementary and integrative medicines such as yoga.

In the past five years, that support, especially for biomedical research, has increased significantly. The number of unique projects funded by NIH grew from 116 in 2015 to 176 in 2019. Similarly, the number of collaborations grew from 197 to 314, and the number of Indian research organizations participating in NIH-funded research grew from 108 to 186. NIAID has also supported research on infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

American and Indian healthcare professionals and academics have worked together at the Center for the Study of Complex Malaria in India, with funding provided by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Photograph courtesy CSCMI team

As attention to mental health issues has grown around the world, U.S. and Indian researchers have been at the forefront. The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, in collaboration with Sangath, one of India’s leading mental health organizations, funded a program on the prevention and treatment of depression. Results from their joint efforts have influenced national and global mental health policy, and will improve access to psychological treatments for depression not only in India, but also in the United States. In addition, USAID is addressing the effects of mental health issues in India. In collaboration with the Harvard Medical School, USAID is working with youth to address the mental health problems resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Building Pandemic Preparedness Strengthened COVID-19 Responses

The United States has worked closely with India to strengthen public health systems in order to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease outbreaks. Over the past five years, the U.S. government has invested approximately $33 million in India to advance the Global Health Security Agenda, a global effort to strengthen the world’s ability to assess and combat threats caused by infectious diseases.

Key activities have included strengthening laboratory capacity and real-time disease surveillance, which has helped India adopt a national policy to better diagnose and treat Acute Febrile Illness and Acute Encephalitis Syndrome. U.S. officials have also helped India pilot its first integrated district public health lab in the state of Chhattisgarh. This approach was adopted by the Indian government in 2020, which now plans to implement it across the country.

Since 2015, the CDC has strengthened India’s public health workforce through the Field Epidemiology Training Program, including support for the India Epidemic Intelligence Service Program, Public Health Emergency Management Fellowships, and the Rapid Response Team. This expanded surveillance and frontline capacity helped detect and respond to outbreaks of the Nipah virus in Southern India in 2018, and hypoglycemic encephalopathy in Northern India in 2019.

This history of successful cooperation shaped our joint response to the COVID-19 pandemic. From the onset of the pandemic, CDC public health scientists supported India’s COVID-19 field response, assisting with technical guidance, contact tracing, diagnostic testing, and infection prevention control practices at health facilities. Hundreds of graduates of CDC trainings have been at the forefront of India’s response, providing on-the-ground expertise across the country.

USAID trained community and frontline workers to combat COVID-19 in India. Photograph courtesy USAID India

USAID has assisted India’s COVID-19 response by providing support to affected people and communities, disseminating public health messages, and financing emergency preparedness and pandemic response. As of November 30, 2020, USAID had helped train more than 46,700 health workers and 79,000 front-line COVID-19 workers, supported 961 healthcare facilities, and worked with the private sector to improve digital health solutions.

In addition, through USAID, the U.S. government donated 200 state-of-the-art, U.S.-manufactured ventilators to 29 facilities, and provided $5 million to support small- and medium-sized enterprises in the areas hit hardest by the pandemic. As of the final months of 2020, the United States had dedicated over $26.6 million in new funding to support India’s response to the pandemic.

U.S. and Indian scientists have collaborated in both the public and the private sectors to jointly develop and test vaccines, diagnostics, and treatments for COVID-19. NIAID is working on countermeasures for COVID-19 through its partnerships in India, including with the U.S.-India Vaccine Action Program. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Indian government have worked together to ensure the safety and efficacy of medical products and to prevent the marketing of unapproved products that fraudulently claim to fight or cure COVID-19.

By fall 2020, several Indian companies had joined U.S. companies and universities to explore the large-scale manufacturing of affordable solutions to the COVID-19 pandemic. These U.S.-India partnerships performed clinical testing and assessments of promising COVID-19 vaccine candidates, including the potential for widespread manufacturing of a vaccine. A number of Indian companies signed licensing agreements with the U.S.-based firm Gilead to manufacture Remdesivir, a potential treatment for COVID-19, for distribution to 127 countries. Such collaboration helps ensure access to safe and effective drugs in low- and middle-income countries throughout the world.

U.S.-India Leadership Tackles the Global Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance

In recent years, the United States and India have increased cooperation on a new threat to global health, antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which occurs when microbes develop immunity to the drugs designed to kill them. Today, U.S. and Indian scientists are studying the pathogens needed to develop medical countermeasures against this threat. U.S. Ambassador Kenneth I. Juster has highlighted the danger of AMR in various fora, including in his 2019 remarks at the inauguration of India’s national AMR Hub in Kolkata, in meetings with Indian policymakers and AMR innovators, and through an op-ed in the Indian press.

In line with India’s National Action Plan on AMR, U.S. and Indian experts have supported the development of state action plans to combat AMR in New Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, and Kerala. The United States has also helped build and support surveillance systems for resistant infections, and develop India’s National Guidelines for Infection Prevention and Control in Healthcare Facilities, which were launched in January 2020.

In cooperation with the private sector, the United States helped fund the Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X), a public-private partnership to incentivize the development of new anti-bacterial cures. In 2019, CARB-X and the Indian Department of Biotechnology signed a Memorandum of Understanding to collaborate on new product development.

Increasing Collaboration on Communicable and Non-Communicable Diseases

During the last five years, the United States and India have strengthened cooperation to combat communicable and non-communicable diseases, with a particular focus on tuberculosis (TB). Because successfully combating TB is a global challenge, USAID and the CDC, in cooperation with the private sector and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, have supported India’s national and local TB elimination programs. Together, the United States and India have cooperated to strengthen multi-drug resistant TB programs, build TB surveillance and diagnostic capabilities, and introduce new TB drugs and treatment regimens.

Joint efforts to support TB research have been central to our search for innovative solutions to the disease. For example, in 2015, funding from NIAID helped establish the Regional Prospective Observational Research for Tuberculosis (RePORT India) consortium. This network of organizations designs and executes clinical research to better understand the TB burden in India, and studies vaccines and therapeutics that could affect TB incidence and prevalence. The success of RePORT India led to its expansion into an International RePORT Consortium that now links scientists and research in Indonesia, the Philippines, China, South Africa, and Brazil.

The United States and India have also addressed jointly a range of non-communicable diseases. The U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) has supported research in India on tobacco control, proteogenomics (the study of proteomic information to improve gene annotation), and affordable technologies for treatment. In addition, U.S. and Indian researchers worked together to support the 2019 opening of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS)-NCI campus in Jhajjar, Haryana, which focuses on cancer research and providing cancer care at affordable rates.

The U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute have supported research on diabetes and cardiovascular disease through Indian centers of excellence. These have included the Madras Diabetes Research Foundation in Chennai, St. John’s Research Institute in Bengaluru, and the Public Health Foundation of India in New Delhi. The centers have led initiatives to control hypertension, address tobacco-related diseases, promote screening of non-communicable diseases, and advocate healthy diets in schools.

Helping People through Improved Health Policy and Systems

As leaders in health innovation, the United States and India have worked on policies to raise national and global health standards. For example, health experts from both countries have collaborated on bilateral and global issues related to digital health.

The United States and India supported the Global Digital Health Partnership, a collaboration of governments, multinational organizations, and civil society organizations to advance digital health interoperability, international data standards, and data stewardship. Through these arrangements, U.S.-India efforts to increase the availability of health data are leading to better care for patients.

USAID has supported the TRACE-TB program (Transformative Research and Artificial Intelligence Capacity for Elimination of TB and Responding to Infectious Diseases), which uses patient data from across India to define disease patterns and suggest solutions. The CDC and AIIMS developed a digital reporting portal that allows tertiary care facilities across India to monitor trends of healthcare-associated infections in order to improve patient care standards.

USAID also contributed to the 2018 rollout of Ayushman Bharat, the Indian government’s national initiative to provide free or affordable healthcare to Indian citizens. This partnership helped train over 24,000 community health officers to support the Indian government’s goal of establishing Health and Wellness Centres across the country.

Growing Contributions to Health from Individuals and Public-Private Partnerships

As two large and diverse democracies, the United States and India have thriving private and non-profit sectors engaged in health and biomedicine that boost innovation, knowledge, and access to quality healthcare. As the connections between our countries have grown, so has collaboration among our doctors, researchers, academics, foundations, healthcare facilities, and private firms.

In the United States, doctors and healthcare professionals of Indian origin have played a particularly prominent role. People of Indian-origin are estimated to comprise 10 to 20 percent of all doctors in the United States. Approximately 40,000 medical students, residents, and fellows at U.S. universities and hospitals are from India, the largest contingent from any one country. The American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin estimates that physicians of Indian-origin service about 30 percent of U.S. patients and provide care for one out of seven people in the United States on a given day.

Increasing numbers of Indian Americans have served in leadership roles in public health in the United States. In 2014, Vivek Murthy became the first Indian American to serve as Surgeon General of the United States, while Seema Verma became the Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2017.

Left: Vivek Murthy served as Surgeon General of the United States, from 2014 to 2017, the first Indian American to hold the position. Photograph by Chris Landsberger © AP Images/The Oklahoman.

Right: Seema Verma served as the Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services from 2017 to 2021. Photograph by Evan Vucci © AP Images

The growth of India’s healthcare sector, including the pharmaceutical industry, has also contributed to increasing connections between U.S. and Indian companies. More and more Indian healthcare facilities are using equipment designed or manufactured in the United States, while an increasing number of U.S. citizens are consuming medicines developed or produced in India. According to the FDA, India was the second largest supplier of drugs and medicinal products to the United States in fiscal year 2019 (October 1, 2018 to September 30, 2019).

The U.S. and Indian governments have sought to leverage this vast pool of talent and resources through public-private partnerships. The Millennium Alliance, a partnership between USAID and the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, has provided seed funding to companies to support the development of low-cost diagnostics and devices for maternal and child health. In 2019, USAID and the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare jointly launched “The Corporate TB Pledge” for the elimination of TB in India, and have subsequently received pledges from more than 100 U.S. and Indian corporations. And USAID has partnered with the National Health Authority to mobilize over $146 million of loans and grants from the State Bank of India and IndusInd Bank, and the Ford, Rockefeller, and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundations to support high-impact solutions for strengthened health systems.

In addition to efforts by our governments, U.S. companies have played an active role in India’s healthcare through innovative financing and corporate social responsibility programs. For example, in 2018, Pfizer and the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi created an incubation accelerator initiative to provide funding and mentoring support for healthcare innovators. Johnson & Johnson Private Limited signed a memorandum of understanding with the Maharashtra state government to address pressing public health issues such as tuberculosis, maternal and child health, and infection prevention.

A Partnership Promising Healthy and Productive Futures

The long history of cooperation between the United States and India in health and biomedicine, which has driven research and innovation, has been both successful and broad-based. It has drawn on the best of the rich human capital and diverse institutions of our two countries. And it has led to longer and healthier lives for our citizens, and those of the world. Together, we are optimistic that we will be able to address the world’s new health challenges in the years to come, and to ensure that our nations are able to thrive in good health.

Building on U.S.-India Success Against the Rotavirus With New Vaccine Research

Photograph by Monica Tiwari/International Vaccine Access Center

Effective vaccines are one of the most potent tools in the fight against infectious diseases. In March 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the ROTAVAC vaccine to protect children from the most common strain of rotavirus, one of the main causes of mortality in children under five years of age. ROTAVAC was the first vaccine fully developed, manufactured, and deployed in India. This historic launch represented the culmination of almost 30 years of collaborative work under the U.S.-India Vaccine Action Program, established in 1987 by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/National Institutes of Health, India’s Department of Biotechnology, and the Indian Council of Medical Research. Following this success, the United States and India are working through the Vaccine Action Program on tuberculosis, dengue, respiratory syncytial virus SARS-CoV-2 (the virus responsible for COVID-19), and other globally-important pathogens.

Giving Sight to Blind Children, While Contributing to Global Knowledge

Photograph courtesy facebook.com/ProjPrakash/

In many scientific endeavors, direct societal benefits come long after the research has been completed. However, in some instances, the process of conducting research directly improves people’s lives. Project Prakash (“Light”), funded by the U.S. National Eye Institute (NEI)/NIH, is one such example. The project has used a combination of behavioral neuroimaging and computational studies to yield important clues about brain mechanisms of learning and plasticity, while simultaneously bringing sight to blind children. Over 42,000 children have received surgical treatment, non-surgical care, and ophthalmic screening through the project. Project Prakash illustrates the power and promise of U.S.-India collaboration and the benefits that can emerge when clinicians, social workers, and scientists work together.

Protecting Newborns from Antibiotic-Resistant Infections

Each year, nearly 60,000 babies in India die from sepsis related to antibiotic-resistant infections. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has been sharing its expertise in infection prevention and control with Indian partners through the Antibiotic Resistance Solutions Initiative. This program seeks to identify the sources of outbreaks in four neonatal intensive care units and then uses innovative, cost-effective interventions to prevent the spread of antibiotic-resistant pathogens and ultimately save the lives of young children.

Keeping Kumbh Mela Celebrants Safe and Healthy

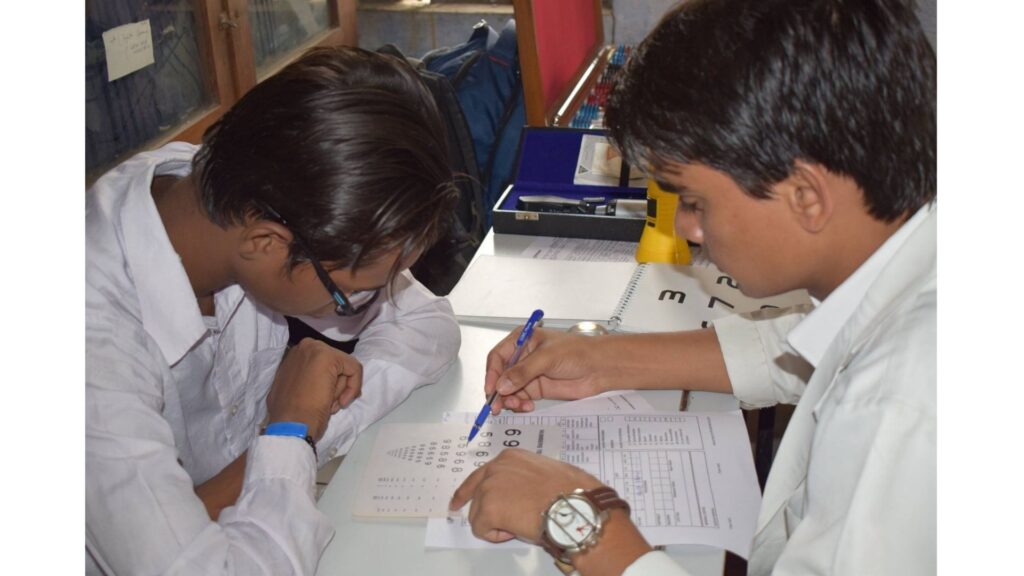

The CDC leads a laboratory training session to prepare healthcare professionals for the Kumbh Mela. Photograph by Indranil Roy

The Kumbh Mela festival, the world’s largest religious gathering, is a time for celebration, but could also present public health concerns. To prevent disease outbreaks and other threats to public safety, CDC worked with the state of Uttar Pradesh and the Indian government to conduct real-time disease surveillance and response during the 2019 festival in Prayagraj. Joint activities included conducting workshops to build local disease surveillance and laboratory capacity; supplying rapid, point-of-care test kits to increase the state’s ability to test for cholera; and establishing a field Emergency Operations Center. After the successful event, CDC and its Indian partners held an after-action review workshop to inform planning for future Kumbh Melas and ensure that celebrations can continue to be held safely.

COMMENTS